Making their way in the world

Ipswich sparrows are generally quite productive on Sable Island. Each pair of birds raises two or three broods every year. Although gulls and crows do raid some nests, Sable Island is free of mammalian predators, so productivity is very high, compared to mainland sparrow populations.

Summer or winter?

Ipswich sparrows breed in nearly all of the habitats on Sable Island, from heathy scrub (dark green in the photo) to sparse marram (beach) grass (light green in the foreground). Breeding output is slightly better in heath than in other habitats, and heath is more densely populated (perhaps because birds prefer it).

But whether a young bird ultimately returns to breed, and whether an adult returns to breed again, does not seem to depend on habitat or weather conditions on the breeding ground. So perhaps it's conditions on migration or during wintering that drives survival -- a tough thing to study!

A technological breakthrough

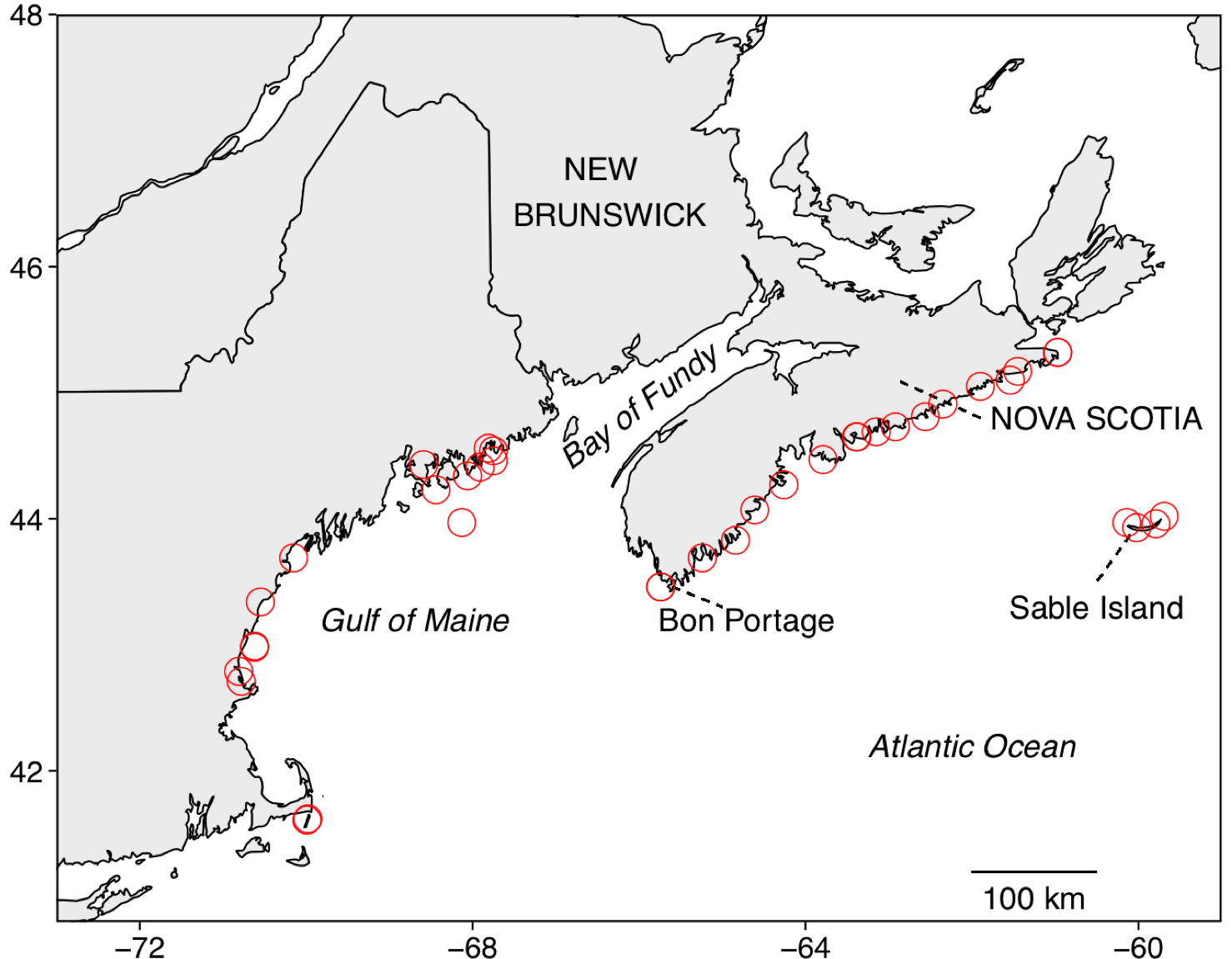

New radio tags have given us a window into the mysterious period between breeding seasons. Weighing less than 3% of the bird's weight, these tags send radio signals via a small antenna on the bird's back, that then are picked up by fixed, solar-powered receiver stations, like this one on Sable Island. Each individual tag sends a distinctive signal, so we can know which bird passed by which station when.

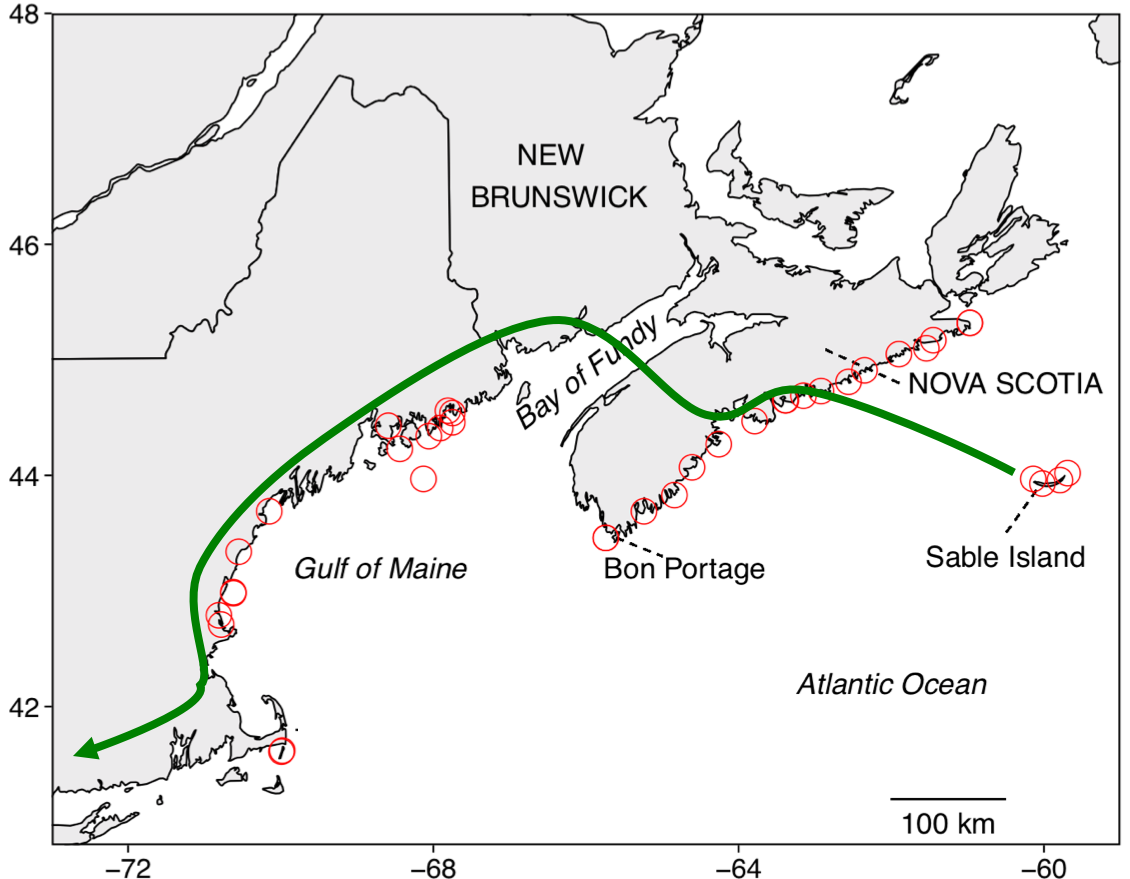

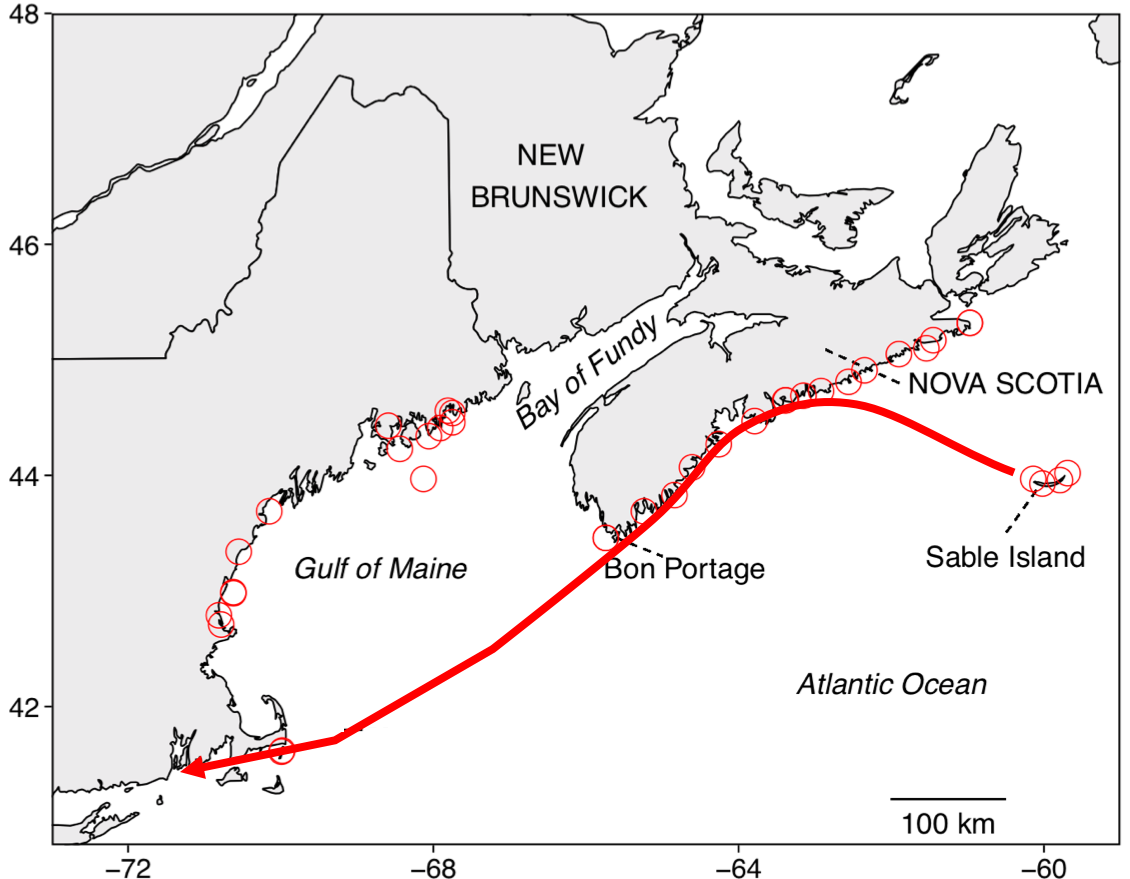

Now that receiving stations are set up all along the East Coast, Phil Taylor and his students at Acadia University, starting with Zoe Crysler, have started to figure out where the birds are going, and when.

A first for migration research

Zoe Crysler's study showed that adults and young birds took different routes. Young birds headed to land, while adults were more prone to take long flights over water. It was the first direct observation of a songbird showing age differences in migration routes.

But many birds, especially adults, simply disappeared. Where'd they go?

It'll take more birds to figure that out. That's where you come in -- whether you're a birder, a beachcomber, or just someone who likes wandering along the winter shore.

Enter the Ipswich Sparrow Project ...